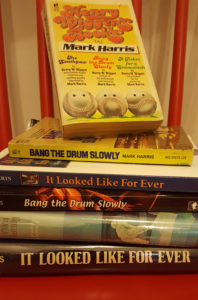

Some of you already know how much I love the Henry Wiggen books and have experienced my constant exhortations to read them. Mark Harris has written the best series of baseball fiction that I’ve ever encountered, and since I know many people who appreciate both baseball and fiction, I find it hard to believe that these books are not more appreciated among this particular subset of humans. They are truly the Dynamo or Show of Force of the sports fiction realm, except the material is more widely available. Sixty years after their publication, the storylines hold up well and the overall themes are still relevant. And all four novels are still in print via the University of Nebraska’s Bison Books.

In order to introduce more readers to the delights of Mount Vernon’s own Mark Harris, I had been thinking of doing a Henry Wiggen-specific blog, rather than a food blog, a book blog, or a combination of the two. Rest assured there will be much more Wiggen content in this particular outlet. But what finally provide the catalyst to write about Henry Wiggen was an unrelated world event, aka the unexpected forced retirement of Alex Rodriguez.

Last Saturday night, we heard that the Yankees had scheduled a press conference for the next morning regarding the fate of A-Rod. Multiple alarms and crazy dreams catapulted me awake in time to watch it live. When it was announced that he would be retiring in less than a week, then staying on with the Yankees as a special advisor, you could tell that he was trying to be gracious and diplomatic but was not thoroughly convinced his playing days were over. In the past week, after his last few games with the Yankees and official farewell on Friday, there have been rumors of him possibly catching on with another team (the Marlins?) in an attempt to make it to 700 home runs or beyond. No matter what you think about A-Rod, it is clear that he is a dude who loves baseball. And while his career was exceptional, his struggle is a common one, regarding players feeling they still have a little bit left, even if their teams and the general public do not concur.

Henry Wiggen experiences a similar scenario in the fourth and final Wiggen novel, It Looked Like For Ever. Published in 1979 but set in 1971, it was written long after the other three Wiggen tales that appeared in the mid 50’s (in order: The Southpaw, Bang the Drum Slowly, and A Ticket for a Seamstitch.) It Looked Like For Ever opens with the death of longstanding Mammoths manager Dutch Schnell and Henry’s subsequent speculation that he will become manager. Instead, upon returning home to Perkinsville after the funeral, he finds out he has been unceremoniously released by the club. Wiggen had been a star for 19 years, but in his fictional case there was no press conference, no speculation and no ceremony.

Like in Bang the Drum Slowly, the other best Wiggen story, For Ever opens with some wintertime travel, first to St. Louis for Dutch’s funeral and then to Japan in a short-lived exploration of continuing his career with the Oyasumi Cobras. Along the way, you are introduced to Henry and his tribulations as a “younger older person.” The 39 year old Wiggen has undergone a stunning transformation since we last saw him in 1956. Not only has he become the father of four daughters, but also a millionaire who has saved scrupulously and multiplied his earnings via savvy investments. Yet he also has prostate trouble and secret contact lenses (imagine the wearing of contacts being an issue in 2016!), and his younger daughter Hilary is distraught at the idea of never having seen him play baseball in the flesh. Her three older sisters have watched him pitch in assorted ballparks, but somehow she had never prioritized seeing him play until it was too late.

Henry vows to catch on with another team in order for Hilary to see him perform. This is the motivation that he repeats throughout the book as the reason behind his comeback: that he is desperate for his daughter to see him play. Though as he continues to pursue one avenue after another to get back onto a major league roster, it becomes clear that Henry himself believes he is still capable of playing baseball.

I had always internally compared Henry Wiggen to Andy Pettitte, in that both were long-tenured left-handed aces and family men (though of course Henry was also a pacifist iconoclast and author, compared to the more conventional and religious Pettitte.) Pettitte himself returned to the Yankees in 2012 after leaving baseball in 2010. He was welcomed back with open arms and contributed significantly in his last two seasons. But Henry’s trajectory in For Ever reminded me of A-Rod’s plight in that he is not quite ready to end his career, and goes to great lengths to achieve that, from traveling to Japan to Washington to Tozerbury to California, and yet ultimately having things not quite turn out the way he expected.

Alex Rodriguez and the fictional Wiggen have a similar goal: to keep playing baseball the way they feel they are capable of, even if no one will offer them a roster spot. However, their other motivations and lives outside of baseball are vastly different. Alex lives and breathes baseball, and aside from his relationship with his daughters, it is the major component of his life. Henry has many interests outside the game, and his curiosity about the world sometimes hinders the perception of whether he is truly dedicated to his comeback. His fascination with Washington manager Ben Crowder’s food-warming dish and questions about Japanese cherry trees cause exasperation to flare at crucial moments while trying to convince those in power that he is still significantly motivated to play. Motivation is a major theme in this book: characters such as California owner Suicide Alexander openly question Henry’s motivation, as do other players and managers. No one seems to believe that someone with eclectic and refined interests like Henry can display the single-mindedness demanded by a comeback at 39.

Alex Rodriguez and the fictional Wiggen have a similar goal: to keep playing baseball the way they feel they are capable of, even if no one will offer them a roster spot. However, their other motivations and lives outside of baseball are vastly different. Alex lives and breathes baseball, and aside from his relationship with his daughters, it is the major component of his life. Henry has many interests outside the game, and his curiosity about the world sometimes hinders the perception of whether he is truly dedicated to his comeback. His fascination with Washington manager Ben Crowder’s food-warming dish and questions about Japanese cherry trees cause exasperation to flare at crucial moments while trying to convince those in power that he is still significantly motivated to play. Motivation is a major theme in this book: characters such as California owner Suicide Alexander openly question Henry’s motivation, as do other players and managers. No one seems to believe that someone with eclectic and refined interests like Henry can display the single-mindedness demanded by a comeback at 39.

The process of balancing Henry’s sense of self as a successful businessman and family man, author and baseball player, and his perception of himself vs. the perception that others have of him, are all essential components in the storyline. Aside from being a skillful southpaw, he’s primarily an outsider, author, skeptic, father and husband. He and Alex are each weirdos in their own way, but Henry’s attempt to juggle all of these elements while pursuing a comeback add both humor and gravity to his story.

Besides the baseball theme, my two favorite elements of Harris’s writing are his use of precise detail and sly humor. Unlike some books, where inaccuracies in plot points or timeline can send me stewing and eschewing the rest of a series, the Henry Wiggen books are painstakingly accurate in their representation of dates, places and characters. You can tell that Harris is a man of details in that he prints the entire 1955 roster in Bang the Drum Slowly (along with players’ full names, birthplaces and armed services records. The birthplaces alone were a dream to me in 1998, and immediately inspired me to take down our atlas and start crafting a fictitious roster of my own.) All of these details, regarding the 1971 circumstances of each beloved character, societal shifts and technological advances, help convincingly move the Wiggen storyline forward by a decade and a half.

A perfect example of the time shift between the last Wiggen book set in 1956, and this one in 1971, is Henry Wiggen owning a car phone. This solidifies his status as a rich man on the cutting edge of technology, and also provides assorted humorous scenarios. When he gets pulled over for driving too slowly, the cop is intrigued by his car phone and uses it to telephone his daughter in Yonkers, who reports she would be more impressed if he was speaking to young phenom Beansy Binz than Henry Wiggen. The car phone is also an essential plot device regarding his friendship with his future manager’s wife, Marva Sprat, and a source of fascination for other potential employers such as Ben Crowder. Call forwarding is also employed in a turning point in the storyline. The phone-related details are all the more enjoyable if you are familiar with the earlier books. Back in 1955 in Bang the Drum Slowly, eavesdropping by operator Tootsie provides a pipeline of essential information, for which Henry trades her two grandstand seats, “third base side, Author, lower deck, not too far back and not behind no pillars nor posts.”

Phones aside, Harris has a good eye for inserting details that reveal how American society has changed between 1956 and 1971 (especially with the additional eight years of perspective between setting the book in 1971 and publishing it in 1979.) Henry’s consternation regarding the casual dress of his young teammates, and slogan-emblazoned t-shirts in particular, culminates in him being presented a shirt bearing the slogan “Dirty Old Men Pitch Relief.” There are references to Wiggen’s hair hanging down his neck, expansion teams, night baseball, and his eldest daughter Michele being on a hijacked plane on her way to India. This potentially nightmarish scenario is mentioned in passing, but with a typically ridiculous Wiggen twist: he ended up negotiating with the hijackers by promising to teach them assorted pitching techniques. (No word on whether that would also work for a PR professional.) However, this may have resulted in his future prostate trouble, as he was unable to take a bathroom break while the ordeal unfolded. What makes all these anecdotes so enjoyable is that they are just side stories, for if they were essential components of the plot, they might be too cartoonish or unbelievable. Conversely, the plots of Harris’s stories are built on everyday human themes and events, making them just engaging enough to devour, yet realistic enough to believe.

The increased popularity of psychiatric treatment also plays a role in It Looked Like For Ever. In an effort to curb her screaming fits, Hilary Wiggen is in the care of Dr. Schiff, a Manhattan psychiatrist who “would be expensive to dress and cheap to feed,” in Henry’s observation, as she seems to subsist entirely on Coca-Cola. Dr. Schiff was recommended by Henry’s former teammate Ev McTaggart (who ended up as Mammoth manager after Dutch), whose own daughter required her services. Henry’s friend and broadcasting partner Suzanne Winograd and her daughter Bertilia are also patients. Dr. Schiff also provides the namesake for one of Hilary’s two horses, the other being Late Manager Dutch, purchased from “the horse lady of Tozerbury.”

It Looked Like For Ever is populated in part by Harris’s beloved cast of existing characters, from the Wiggen family to the Moors family establishment. However, many of the central figures in this fourth installment appear here for the first time. There are a number of new female characters, from Hilary to Dr. Schiff to Marva Sprat to Henry’s lawyer Barbara, and new baseball men, from Ben Crowder to Jack Sprat to Suicide Alexander. But they are all drawn in classic Harris style and carry the series forward authentically. In my own writing, I always worry about my characters having adequate motivation, but Harris has no similar issue, as motivation is a major topic in the book, in particular regarding Henry’s being questioned. It is perhaps a relic of the time that team executives would be so concerned regarding proper motivation of individual players, versus the present day when most organizations are desperate for capable left-handed relievers. (I am sure no one was questioning the motivation of Jesse Orosco when he was still pitching at age 46.) But due to a series of misunderstandings along with his own earnest actions, Henry’s motivation is deemed sufficient at last. “Any 39 year old millionaire that will steal 1/2 a bag of golf clubs off me at a dead man’s funeral is my kind of man.”

Most existing characters have ended up with fates appropriate or predictable in this last installment. I was only disappointed in the story of Perry Simpson, and that early characters such as Mike Mulrooney and Bradley Lord did not reappear in the 1971 World of Wiggen. The satisfying output that is It Looked Like For Ever is a marked contrast to The Lyre of Orpheus, Robertson Davies’s disappointing and almost unreadable conclusion to the Cornish trilogy, perhaps because there was never a set number of books planned in the Wiggen series. I will always be curious what compelled Harris to go back and produce one more, years after the others were completed (and conveniently, also after his own autobiography and Norman Lavers’s critical study covered them.) In Harris’s autobiography Best Father Ever Invented, he recounts an attempt in 1959 to write one more Wiggen book, set entirely during the seventh game of the World Series. But “I feel challenged to write ‘the great baseball novel.’ It died. A year later, I tried again, and again it died.” Twenty years later, what changed? Perhaps writing the script for the movie version of Bang the Drum Slowly, and envisioning Henry’s story in a modern world, compelled Harris to revisit these characters one last time.

One of the many reasons that It Looked Like For Ever may actually be the best Wiggen book is that its sense of humor is darker and more evolved than in prior stories. (Bang the Drum Slowly, in comparison, couldn’t feature too many jokes involving death due to Bruce Pearson being doomded [sic].) It Looked Like For Ever displays Harris’s ever-refined wit, and while there are many comical scenes, from Henry and Holly’s visit to the non-town of Oyasumi, to Henry’s shortlived broadcasting career, most of the best jokes involve some form of mortality. When the Wiggenses take Hilary to St. Louis for Dutch’s funeral and people ask her “and what are you going to get for Christmas, my little lady?”, she replies, “I am getting to see a dead man at last.” The scene at the Foucault Pendulum in San Francisco is another great example of Harris’s humor in that it is funny and deadly serious at the same time. From amidst the crowd waiting for the pendulum to knock down the pegs, Hilary leaps up and screams “You might be dead before you ever play baseball again,” causing a massive disturbance involving crying children and frantic museum guards, before becoming immediately ladylike, watching the pendulum knock down the peg, and sighing “at last.”

Along with liberal sprinkling of dark humor, Harris is a bit more plentiful with the Westchester references in this final Wiggen installment, probably due to the fact that Henry is spending much of his time at home while traveling back and forth to the city. He is pulled over on the Taconic, he drives on the Bronx River, and references passing through Port Chester and Mount Vernon. Port Chester is also fictionally represented as Henry’s hometown of Perkinsville, which, from its description, I would have originally surmised to be further up the line and a fictionalized version of something more like Poughkeepsie. But I guess in the fifties, Port Chester was more separated from the city, physically and culturally, than it is today. Coincidentally, I was obsessed with this series of books a full ten years before becoming a Mount Vernon resident (and discovering that Mark Harris hailed from Mount Vernon, but that is a story for another day.)

In this fourth and final installment, Wiggen is still a bit of an unreliable narrator and speaker of his own unique vernacular, despite his overall increased level of sophistication. He manages to spell the word souvenirs correctly once earlier in the book regarding Old Timers Day, but by the final page he is back to representing it more inventively. It is perfectly placed in a final sentence that appropriately ties up the mood of the series, in the last words ever written about Henry Wiggen by Mark Harris’s hand. Harris passed away in 2007, erasing the potential for additional Wiggen installments years after the fact, in the manner that got us It Looked Like For Ever. Though with Alex Rodriguez, we have no such equivalent finality, as there is still a chance that someone will sign him and further his quest for additional playing time and a shot at 700 home runs.

When my dad gave me the Henry Wiggen’s Books trilogy back in eighth grade (his edition predated It Looked Like For Ever), he said to start with Bang the Drum Slowly, then go back to The Southpaw, the first book in the series. This is still the order in which I instruct potential Wiggen acolytes to read the series: 2, 1, 3, 4. But if this too-long treatise on It Looked Like For Ever piques your interest and you must begin with the final Wiggen novel, I would still consider it a job well done, Run the Jewels style.